|

| Randall Tate Photography |

And now for a good old fashioned adventure.

Randall and I left Seattle for Bellingham before 5am, and were eagerly anticipating the sun rising for the journey. It never did, and we ended up killing time in a Fairhaven coffee shop, and then in the American Alpine Club classroom for the first hour of lessons before the world lit up even a little bit.

|

| Randall Tate Photography |

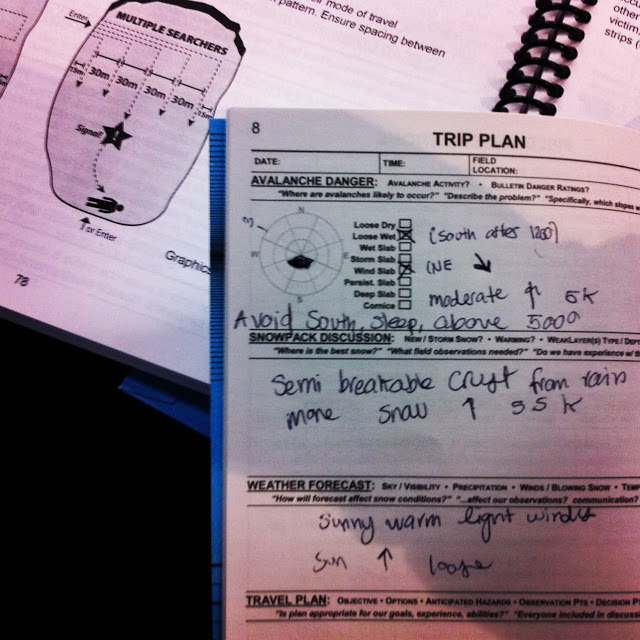

For the next two days, we carved pits into the snow with shovels and saws and toured the back country of Mt. Baker. At the time, Baker had the most snow of anywhere in North America, although I'm not sure how long that lasted, because Friday night Stevens Pass to the East was buried at a rate of about two feet in an hour, and The Stoked were bemoaning not being there. I'm not sure what we could have done with anymore powder, however. As it was there was already too much of it.

We took turns breaking trail, thank goodness, but either way all movement was exhausting. If, during transition, I placed a single boot off the skin track, I'd fall up to my neck in snow. It would take a day's ration of energy to swim to the surface and right myself. Skiing downhill in untracked powder was a wild rush, and mentally taxing only because the fear of falling translated into the fear of writhing helpless in the snow, carving an ever deepening hole, for an embarrassing long time, for the snow was feather soft and endlessly deep. Other than that the days were peaceful, snowing consistently, a completely quiet, cold world which I observed from the depth of four hooded jackets and the pink-tinged blur of fogged goggles.

That particular avalanche class, although not our first choice (our original class, a yurt trip powder cat trip, was cancelled because of dangerous conditions) was a momentous occasion as we shared three days with Lyle, who I've since come to know to as Lyle Who is All That is Man. Lyle is a mountain guide, a structural firefighter in Seattle, and a former Alaskan longshoremen fishermen. Had he also been a pediatric surgeon it would not have surprised me the slightest. He spoke very quietly and politely, almost as if he were trepidatious of being the center of attention, which is funny because Lyle should be unsure of nothing, ever. Randall and I loved Lyle.

|

| Randall Tate Photography |

The other instructor was a man named Dustin who very much looked the part: he had cheek bones chiseled from ice and stained rose from the wind. Dustin was very quick to make a joke, and brush off the dust from my sweater when I dropped it on the ground, and talk with great about the 'suffering' of guiding on Denali. Randall and I both know the outdoor guiding well, and we felt very fortunate that we avoided entirely the douche-baggery we both slightly expected from our instructors. They were in fact very patient and cheerful and certainly most enjoyable to look at.

That weekend we stayed at the Mountaineer lodge, which shown warm-bright under a heavy frosting of snow. We shared the lodge with The Stoked and also a handful of similarly windblown and healthy young skiers and three snowboarders who had an affinity for curling up in slippers near the wood stove with their nose in guide books, discussing with great revelry their most recent trip to Peru. (Or perhaps it was Patagonia. Or Perugia?) When I went to bed at 10pm they were thus engaged and when I woke up at 6 there they were, in the same positions, with the same boundless enthusiasm, as if they were barely aware that sleep as a state existed in the first place, much less that it was considered a necessity by some.

And so we found ourselves, after ten hours of pushing through relentless powder, skinning up and gliding down hills and chopping countless pits into the drifts, presented with glitter paint, brushes, and an entire window each on which to paint. True to her world, the round woman baked nut cookies, a strawberry cake iced with cool whip and a bowl of Hawaiian punch mixed with ginger ale that when added up, although sickening with regards to sugar accumulation, created an atmosphere so wholesome and sweet I nearly died.

For a little while it was completely quiet as all of us painted on our panes of glass, everyone in sweaters and long underwear, deeply concentrated. The Stoked surprised me by painting four separate lovely designs, mountains and skiers and one Santa Claus surfing a wave, done up in marvelous detail. A family with two tiny red haired girls climbed up on furniture and painted a snowman three panes high. The only window that did not register close to outstanding was that belonging to Randal and I, but mostly me; I'd painted a house floating on the black sky outside the window, and a few small stars and snow drifts, and then I'd lost all inspiration. I'd have filled the whole thing up with snow but the children had all the white paint and weren't giving it up, so I filled the rest of the window with blue. All Randall really added was a stencil of a pine tree in the middle of the air, and everybody asked if our house was a tribute to the Sandy flood victims, which was never the intent.

I slept very well at the lodge, the strain of snow struggle tugging my body into a white, heavy underworld. Randall on the other hand had a different story to tell and claimed that I snored. Which is the most ridiculous thing I've ever heard in my life, since I'm a crystal quiet sleeper. Snoring drives me crazy and I would never do it.

|

| Randall Tate Photography |

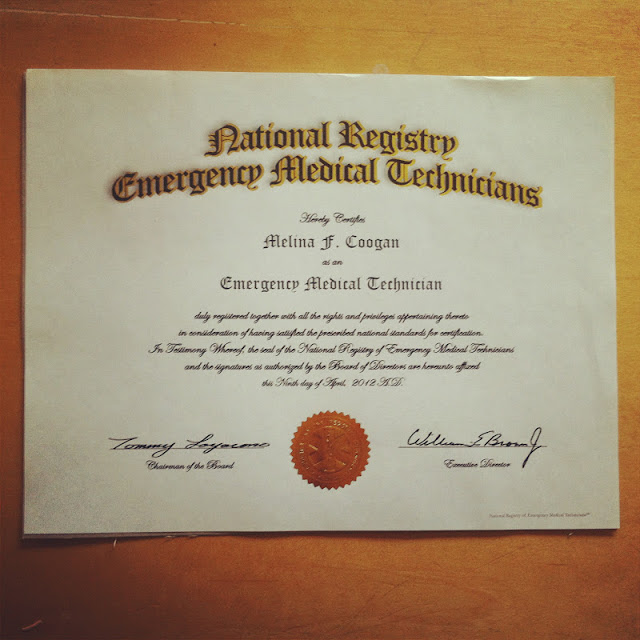

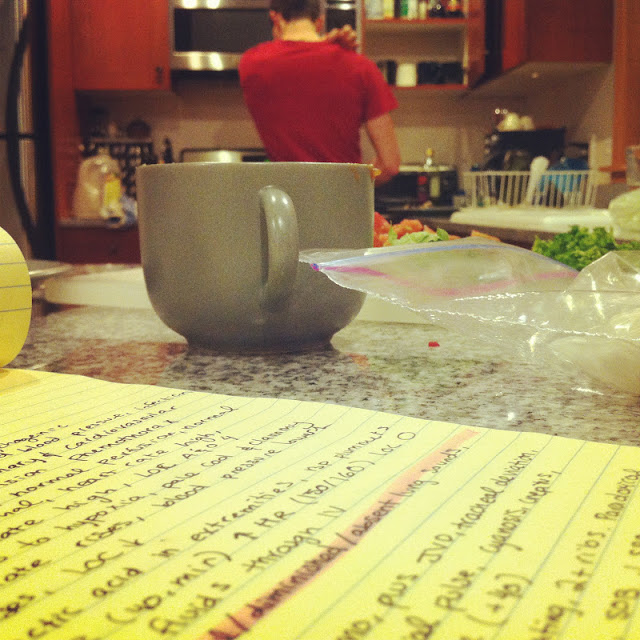

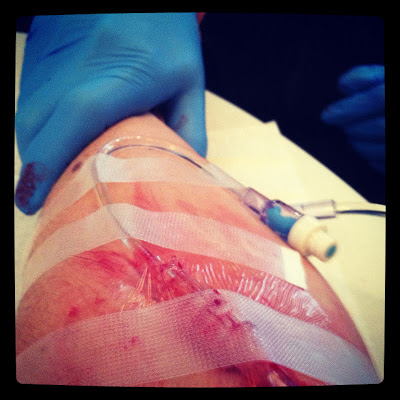

Aside from that, I can't say the weekend could have at all been improved. We are all Avi I certified now, with Randall and I a few hours closer to continuing our N-EMT registration for another two years.

It concluded, as all good things do, with pints of porter at a ski bar with an overcrowded table and seven hungry souls ordering plates of hot food and talking about upcoming adventures. I challenge you to find a worthy weekend that does not end in such a manner.